- Best Stump Killer To Consider for Your Yard - January 5, 2024

- The 7 Best Spading Fork Options - December 21, 2023

- Best Head Planters – Top 24 Options You Will Love - December 16, 2023

The USDA Planting Zone Map is a reference map to help determine which plant varieties will thrive in different parts of the country. The map is divided into four planting zones:

- Zone 1: USDA Plant Hardiness Zone A (degrees Fahrenheit)

- Zone 2: USDA Plant Hardiness Zone B (degrees Fahrenheit)

- Zone 3: USDA Plant Hardiness Zone C (degrees Fahrenheit)

- Zone 4: USDA Plant Hardiness Zone D (degrees Fahrenheit)

The map also contains a legend and helpful tips and information. Michigan planting zone map is an excellent tool for knowing which crops to plant depending on your geographical location.

A Michigan planting zone map divides the state into six different zones. Knowing your specific zone can help determine what types of plants will grow best in your area and the time of year that you need to start planting for a successful harvest.

To find your planting area on the map, you can click to enlarge the map and scroll to your general part of the country. For example, Michigan’s plant map includes zones 4a, 4b, 5a, and 5b. However, there are warmer pockets in the state that have zones 6a and 6b.

The growing zone where you live is essential for selecting the best plants for your garden. Within each growing zone, there exist different microclimates. Those come from local landscape features such as hills or valleys or hardscape elements like buildings and sidewalks and affect plants and other organisms in the area.

Different factors, such as the winter sun, wind, humidity, and soil nutrients, will play a role in determining how hardy a plant is during winter. The USDA planting zone map is one of the most valuable tools for determining where to plant your plants.

The warming climate across Michigan and most of the Great Lakes region may result in warmer winters which will be more favorable to gardeners.

The US Department of Agriculture creates plant hardiness zone maps. With that, they display the prospect for the average temperature in a long time. Different plants thrive in different cold levels.

Further research by ClimateCentral.org reveals that hardiness zones are flowing north with the warming trend of the past 20 years; this includes Marquette as the data point for the Upper Peninsula that serves as one of the odd exceptions to this trend.

USDA Hardiness Zones from 1981 to 2010

Here is the most recent official USDA hardiness zone map for the period that ended several years ago. The temperatures have warmed more, on average, in most areas since that time. As a result, Zone 6 has expanded into much of central Lower Michigan and even up the western shoreline in Michigan. Zone 5 has moved into the northern Lower Michigan’s cold areas.

There has been a significant amount of warming in Detroit’s annual low temperatures since the 1970s. This case would now leave an Ohio plant that can tolerate cold temperatures able to grow in Detroit.

The yearly low temperature in Grand Rapids has increased by 5°F over the past 40 years. According to the latest data by Climate Central, Lansing is now expected to only get down to 10 below zero, which compares favorably with the 15 it formerly hit in the 1970s.

Flint has experienced some cold weather the past few years. The average lowest annual temperature was higher than usual until around 2010, and it dropped back down. Like other mid-Michigan cities, Saginaw has experienced its coldest winter temperature warming.

Traverse City has warmed considerably over the past 30 years. The average annual lowest temperature is now 8 degrees C warmer than in the 1970s.

Alpena also shows the last 30 years’ warming trend. The data from Marquette shows that the city is not warming. In contrast, the lowest temperatures have been going the opposite direction and have been getting colder. It’s unclear to many experts why the temperature of Marquette would be substantially colder than the rest of Michigan.

Geography of Michigan

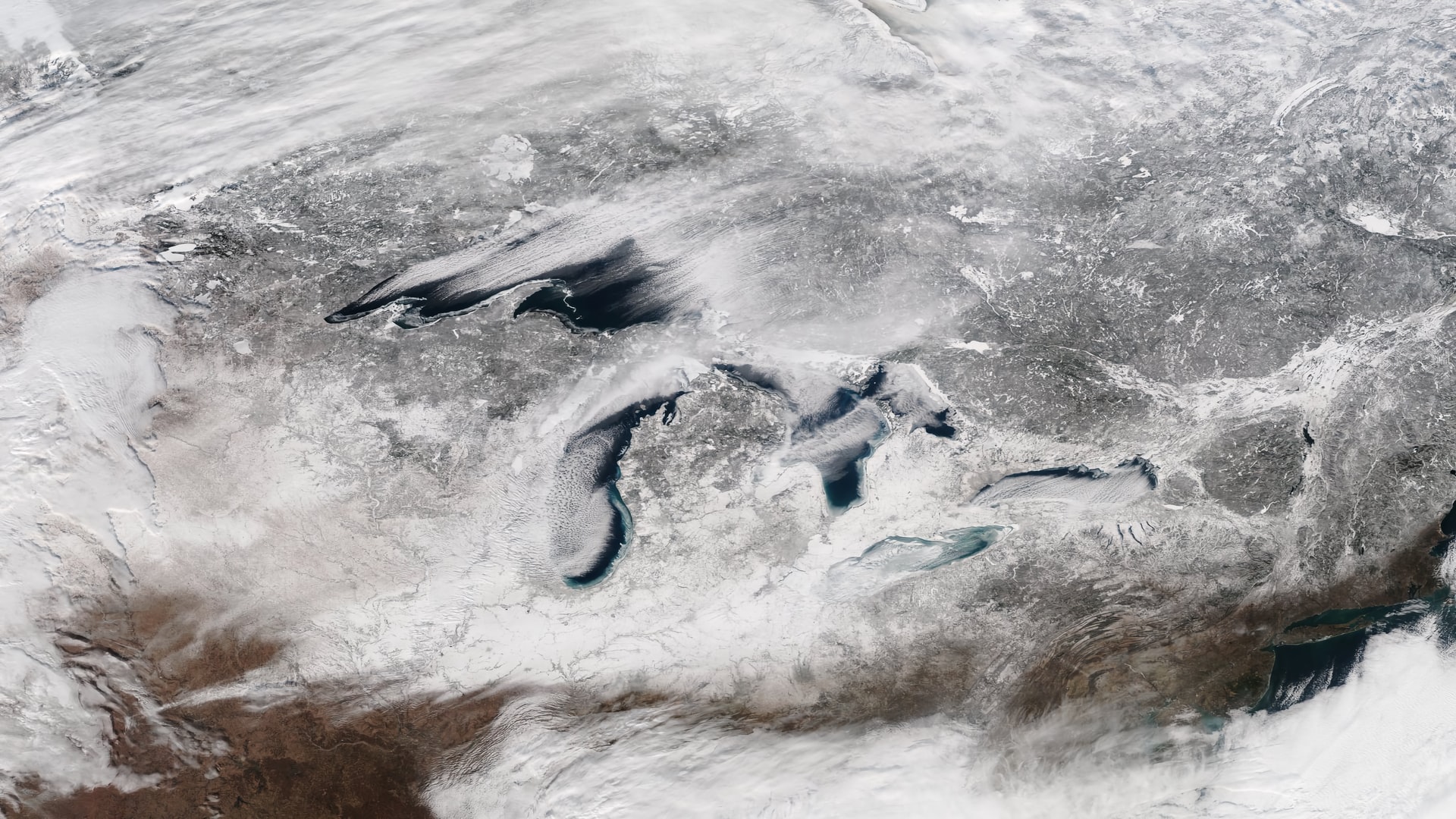

There are two peninsulas in Michigan and many nearby islands and Great Lakes surrounding these peninsulas. The Wisconsin southwest bounds the Upper Peninsula, and the Ohio and Indiana south bounds the Lower Peninsula.

These two landmasses are separated by the Great Lakes’ waterways of the Canadian provinces of Ontario and with Straits of Mackinac. Since the Great Lakes surrounds Michigan, flowing into the Saint Lawrence River, the state has rivers and streams nearly within the Great Lakes – St. Lawrence watershed.

The smaller parts of Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair and roughly half each of Lake Huron, Lake Michigan, and Lake Superior consist of Michigan’s territorial waters, including Around 11,000 inland lakes. It also includes 1,305 square miles of inland waters, 38,575 square miles of Great Lakes waters, and 58,110 square miles of land.

Therefore, it compares to Alaska regarding its territorial waters. As the eleventh largest state in the country and the east Mississippi River’s largest state, Michigan encompasses 97,990 square miles total area, including territorial waters.

Therefore, the forest parts of Michigan are more than half of the state’s land area, totaling 30,156 square miles. Michigan lies between 82 degrees and 91 degrees west longitude and between 41 degrees and 49 degrees north latitude.

Great Lakes

Lake Superior, Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, and Lake Erie form most of the water boundary of the Great Lake. In addition, the state boasts about 150 lighthouses that are more than any state, as it shares water and land boundaries with Indiana and Ohio, which are on the southern part of the state.

The state’s northern boundaries are nearly entire water boundaries, with Wisconsin and Illinois in Lake Michigan and the Upper Peninsula and Wisconsin serving as a land boundary. Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Lake Superior serve as water boundaries to the west, with Ontario in Canada to the east and north.

Michigan streams and rivers drain wholly into the Great Lakes, except two tiny regions on its borders, the Kankakee-Illinois Rover in the Lower Peninsula and the Mississippi River in the Upper Peninsula by way of the Wisconsin River.

Michigan’s largest islands include Charity Island, Bois Blanc Island, Mackinac Island, Les Cheneaux Islands, and Drummond Island in Lake Huron, Sugar and Neebish islands in the St. Mary’s River, Grand Island, and Isle Royale in Lake Superior. Groose lle and Belle Ise in the Detroit River, Harsens Island in Lake St. Clair, South Manitou Island, Fox Islands, and Beaver Island in Lake Michigan.

The Upper Peninsula’s principal bays are the Big and Little Bay de Noc, Whitefish Bay, and Keweenaw Bay. The Lower Peninsula contains Saginaw, Thunder, and the Grand and Little Traverse bays. Michigan boasts about 3,288 miles of shoreline, coming after Alaska, with more than 1,056 miles when include islands, approximating the entire Atlantic Coast to Florida from Maine.

Lower Peninsula

The Lower Peninsula is mitten-shaped and occupies more than Michigan’s two-thirds land area, with about 195 miles from west to east and 277 miles long from south to north.

The peninsula’s surface is typically level, with glacial moraines and conical hills breaking it and typically not more than some hundred feet tall. The Lower Peninsula’s highest point is either one of the many points close to the Cadillac vicinity or Briar Hill at 1,705 feet. Lake Erie is the lowest point at about 571 feet.

Michigan’s feature is the Thumb, which endears it the district shape of a mitten. The peninsula projects into the Saginaw Bay and Lake Huron. The Thumb’s geography is primarily flat, with some rolling hills, and the Northern Lower Michigan region is in the Leelanau Peninsula.

Upper Peninsula

The western mountainous Upper Peninsula is heavily forested. The Porcupine Mountains rise to about 2,000 feet altitude above sea level. They are part of the oldest mountain chains globally, forming the watershed between the streams flowing into Lake Michigan and Lake Superior.

Either side’s surface is rugged and Mount Arvon, at about 1,979 feet in the Huron Mountains northwest of Marquette, is the state’s highest point. The peninsula’s side is as big as the combination of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Delaware, and Connecticut, but with fewer than 330,000 inhabitants.

Michigan’s peninsulas’ geographical orientation makes for a far distance between the state’s end. Thus, the Ironwood lies 630 highway miles from the Lower Peninsula’s southeastern corner of Lambertville in the distant western Upper Peninsula. Moreover, the Upper Peninsula’s geographical isolation of population and political centers makes the UP economically and culturally distinct.

Michigan Climate

As a United States’ constituent state, Michigan ranks the 11th in terms of total area, increasing its area jurisdiction considerably with the inclusion of the Great Lakes waters.

Lansing is the state’s capital, which happens to be one of the states in the US with two large land segments; the mineral-rich but sparsely populated Upper Peninsula that lies eastward, from northern Wisconsin between Michigan and Lake Superior, and the Lower Peninsula with its mitten-shaped section that reaches northward from Ohio and Indiana.

Most Michigan residents can locate parks, regions, routes, towns, and other Lower Peninsula features through an upturned right hand that serves as a ready-made map. “Big Mac” has connected the two landmasses since 1957. It is a 5-mile Mackinac Bridge around the Straits of Mackinac that separates the eastern side of Lake Huron from the western side of Lake Michigan.

The Canadian province of Ontario separates the Lower Peninsula in the southeast between Lake Erie and Lake Huron. The St. Marys River forms the international boundary between Ontario and the Upper Peninsula, flowing from Lake Superior to Lake Huron.

Land

Soils

Michigan’s soils vary based on several factors, such as wetness, vegetation, landform, and climate. The moisture is primarily a texture function, including many combinations of clay, silt, and sand at the water table depth. Extensive agriculture boosts fertile loams and clays in the southern Lower Peninsula as the northern Lower Peninsula contains less productive dry sandy soils.

There are some fertile areas in the Upper Peninsula. However, the site has sandy or similar soil like the northern Lower Peninsula or swampy and wet. The western Upper Peninsula soils are rocky and acidic, making that area unsuitable for cultivation.

Michigan boasts muck and peat soils formed from inland plains, flats, and lakes that become filled with organic matter. These soil types are prominent in the eastern Upper Peninsula. However, they are also in the Lower Peninsula and are essential for growing vegetables and planting turfgrass.

Many parts of the state have discovered that they need subsurface drainage to make wet soils productive and tillable. In addition, most of the sandy regions of the Lower Peninsula have also found it necessary to have overhead irrigation as a means of augmenting yields on sandy and dry but otherwise productive gardens.

Drainage

While Michigan is surrounded by water, the state boasts an abundance of waterways, wetlands, swamps, and inland lakes. It consists of about 11,000 inland lakes that are primarily glacial in origin, with a range of size from about one acre to almost 20,000 acres of Houghton Lake in the Lower Peninsula’s north-central.

Michigan’s rivers drain Michigan’s high interior as they are generally narrow and shallow. The Lower Peninsula’s southern area takes most of the larger rivers that flow evenly year-round. The Upper Peninsula contains plentiful snowfall, and higher elevations see several rivers possessing a pronounced peak discharge during the spring with melting snow.

While many rivers in the Upper Peninsula have waterfalls, the ease of portaging and the state’s waterways navigability encouraged early settlement. As a result, Michigan’s rivers are short when compared with the rivers of nearby states. These rivers have less than 150 miles with the distances to the mouths of the major rivers from the headwaters.

Relief

The low elevations and mildly rolling terrain that characterized much of the state’s countryside appealed to early agricultural settlers in Michigan. The Lower Peninsula’s highest point is close to Cadillac, and it rises to around 1,700 feet. However, many parts also have almost featureless, flat plains, the floors’ vestiges of large glacial lakes that existed about 14,000 years ago.

Settlers in the mid-19th century encountered malarial swamps in these flatlands that deterred them. They were also the source of much angst for early growers. Swamp draining was a tiring process that happened to yield highly productive farmland since then. In addition, Lake Michigan encountered giant dunes with several parts of the eastern Upper Peninsula, and northern Lower Peninsula wooded.

The Upper Peninsula’s western part belongs to the Superior Upland, stretching westward from the Upper Peninsula and lying to the south of Lake Superior across Minnesota and Wisconsin. The Porcupine and Huron mountains are rock-cored hills that offer more relief, with the Hurons peak rising to more than 1,900 feet.

What Climate Change Means for Michigan

There are incidents of many changes in Michigan’s climate. The last century has seen most states having warmed two to three degrees F with more frequent heavy rainfall and melting ice cover on the Great Lake. As a result, there will be more scorching days in the coming decades in Michigan that can harm corn harvest in rural areas and public health in urban settings.

The earth warming is changing the climate, and there has been an increase of about 40 percent in the amount of carbon dioxide since the late 1700s. in addition, there is a rise of other heat-trapping greenhouse gases, which have lowered the planet’s atmosphere and warmed the earth’s surface during the last 50 years. There is also an increase in average rainfall, humidity, and heavy rainstorm frequencies in several places with the increase in evaporation.

The world’s ice cover and oceans are even changing with the impacts of greenhouse gases. Carbon dioxide creates carbonic acid by reacting with water. As such, our oceans are getting more acidic. The last 80 years have seen the oceans warming to about one degree.

With that, experts have not been able to decode the water levels in the Great Lakes as the warmer temperatures result in the rise in sea level. Warmer air even melts snow and ice earlier in spring.

Heavy Flooding and Precipitation

Michigan is likely to experience climate changes that will increase the frequency of floods. Midwest’s average annual precipitation within the last century has intensified to about 10 percent. However, there have been about 35 percent in the rise of rainfall during the year’s four wettest days.

Therefore, annual precipitation and spring rainfall are likely to increase during the next century, with the intensity of severe rainstorms. Any of these factors can further increase flooding risk.

Agriculture

There are harmful and beneficial impacts on farming from climate change. The wheat yields will increase during an average year with longer frost-free growing seasons and atmospheric carbon dioxide higher concentrations. The Lower Peninsula in Michigan will likely have about five to fifteen more days in the year with temperatures above 95 degrees F seventy years from now than it has today. More severe floods or droughts would also harm crop yields.

Ecosystems

Animal and plant ranges are likely to change with climate changes. For instance, Michigan’s forest compositions can change through the warmer weather. As a result, the population of black spruce, balsam fir, quaking aspen, and paper birch may decline in the northern Lower Peninsula and Upper Peninsula as pine trees, hickory, or oak becomes more numerous.

Fish habitat will also their dose from the climate change. The available warm-water fish habitat like bass will increase with rising water temperatures and shrinks the available coldwater fish habitat like trout. In addition, increasingly severe storms and declining ice cover would harm the two types of fish habitat through flooding and erosion.

Great Lakes

Climate changes will likely harm Lake Michigan and Lake Erie water quality. Warmer water can even cause more algal blooms, degrade water quality, harm fish, or be unsightly. For example, a Lake Erie algal bloom of August 2014 prompted the Monroe County Health Department to advise residents in four townships not to drink or use tap water for cooking.

The number of pollutants increases from severe storms as it runs from land to water. As such, when storms become more severe, it will increase the risk of algal blooms.

Sewers can also overflow into rivers and lakes through severe rainstorms, threatening water supplies and beach safety. For instance, almost 10 billion gallons of water overflows in southeastern Michigan due to the August 2014 heavy raindrops, ending up in Lake Erie and Lake St. Clair.

Severe rainstorms could cause sewers in Chicago and Milwaukee to overflow into Lake Michigan more often, polluting Michigan beaches.

One of the benefits of climate change is reducing the number of days that ice prevents navigation during warmer winters. For example, ice cover decline lengthened the shipping season between 1994 and 2011 on the Great Lakes by eight days.

Warming could even hurt ecosystems when it changes the timing of natural processes like flower blooming, reproduction, and migration. For instance, migratory birds arrive earlier in the Midwest during the spring than they did more than 40 years ago.

Native Plants for Michigan Landscapes

Robust woody shrubs and trees serve as a strong foundation for beautiful landscapes. Several native plants can enhance wildlife habitat and offer natural beauty beyond the widespread array of easy-to-find exotic plants.

In addition, when adequately placed or chosen, native plants can benefit your environment through less fertilizer or pesticides and reduced water use. Essentially, native plants can lead to less work, increased plant hardiness, and lower long-term maintenance costs.

When considering natives, it may not be true when people assume that you don’t need to worry about maintenance or caring for them. On the contrary, native plants require adequate maintenance and care.

How to Succeed with Native Plants

The essence of succeeding with native plants is to select plants that match site conditions carefully. Unfortunately, several native plants tend to be habitat-specific, even though many of them are tremendously adaptable to a wide range of environmental conditions.

Before choosing plant material, you must know and understand your sites, such as use history, weed problems, moisture conditions, fertility, pH, soil texture, and exposure. Then, ensure to match the site’s conditions to your plant’s natural habitat. Fertilization, mulching, soil amendments, and other techniques can help correct some discrepancies. However, these conditions may not overcome a poor match between your chosen site and the plant.

Also, you must understand that most residential sites like urban areas may not resemble original site conditions, even though your landscape is likely to be in the plant’s native range. For instance, it could be that they have disturbed the soil, or they have placed subsoil on the surface.

Canopy tree removal that provides shade, salt runoff, pollution, and compaction may alter sites further. The native species growth and survival potential in these conditions may not be worse or better than non-native species.

You might need to consider plants that are wet or native soils for urban gardens. Surprisingly, many plant natives to river bottomlands are amazingly adaptable to urban conditions. These plants’ natural environment makes these plants enormously fluctuate in oxygen and soil moisture. Researchers say native plants can adapt to overly wet, overly dry, or compacted soils common to urban areas.

You may consider some of these native shrubs and trees for Michigan landscapes.

Common Paw Paw

Common Paw Paw (Asimina triloba) is around 15 feet tall, and it has a short trunk as a small tree, spreading branches to form a dense round-topped or pyramid head. The tree has a tropical appearance with its dark green, large summer foliage. Brownish-black, edible fruit tastes like a banana, high in vitamins A and C. Grow more than one variety for pollination and even use it along the water’s edge or naturalizing.

Alternate Leaved Dogwood

Alternate Leaved Dogwood (Cornus alternifolia) is about 15 to 20 feet tall, and many growers always overlook the plant regarding landscape consideration.

It provides a fantastic horizontal branching pattern that performs magic in breaking up the landscape’s vertical elements. The plant bears bluish-black berries and clusters of small white flowers. Fall times bring the leaves turning reddish and partial shade is suitable for the plant but thrives well in full sun.

Juneberry, Serviceberry

Juneberry, Serviceberry (A. Canadensis and Amelanchier laevis) grows to about 20 feet tall, and it is easy to grow as it provides an excellent landscape. It also offers year-round awesome and interesting edible fruit. You will also find this plant great along the foundation, specimen plant, or the natural border; as an understory tree common in the countryside when in flower, it prefers partial shade or full sun.

Best Vegetables for Michigan Climate

You will have ample choices for vegetables to grow in your garden if you live in Michigan. However, if you are in Detroit, you are in the USDA Hardiness Zone 5. It is typical to experience cold and frost weather and has a shorter growing season than southern states. Therefore, you will need to select the best vegetables to grow to ensure a bountiful harvest.

Here are a few best vegetables to grow in Michigan;

- Cabbage – you can have a few cabbage heads in your garden as a cooler weather plant that can thrive well in Zone 5.

- Radishes – if you are looking for the fastest plant to grow, one of your best bets is radishes, and you can harvest some varieties in three weeks.

- Cucumber – cucumbers are another excellent veggie for your Michigan garden if you love pickle plants. Essentially, pick a suitable location because cucumbers grow up fences vertically.

- Broccoli – broccoli will grow well in Zone 5 since it prefers moist soil and cooler temperatures.

- Peas – Peas are an excellent summer plant, and they grow as bush or pole beans. If you want to conserve your space, peas are your best plants.

- Green Beans – green beans are another summer plant that will grow up to a trellis or fence.

- Zucchini – zucchini needs about 60 to 70 days from planting to harvest as it grows fast.

- Lettuce – lettuce can grow well in Michigan as a cooler weather crop.

- Tomatoes – tomatoes plants are not frost-hardy as the summer gardening quintessential vegetable.

- Carrots – the entire state of Michigan is perfect for growing carrots, and they require non-compact, well-draining soil.

- Sweet Corn – sweet corn requires about two to four inches apart in rows and full sun to thrive well. Since many sweet corn varieties are frost and hardy tolerant, ensure to plant them in mid-April.

Michigan Vegetable Planting Calendar

It is essential to know the correct time of getting the most out of your garden when planting or transplanting vegetable seeds. You will also have the right time to start your vegetable seeds when you know your first and last frost dates.

Michigan First and Last Frost Dates

| City | Last Frost Date | First Frost Date |

| Ann Arbor | 5/3 | 10/7 |

| Battle Creek | 5/20 | 9/21 |

| Clinton | 5/13 | 10/9 |

| Dearborn | 5/2 | 10/13 |

| Detroit | 5/2 | 10/13 |

| Flint | 5/6 | 10/8 |

| Grand Rapids | 5/15 | 9/29 |

| Holland | 5/8 | 10/10 |

| Kalamazoo | 5/10 | 10/3 |

| Lansing | 5/6 | 10/8 |

| Livonia | 5/3 | 10/7 |

| Sterling Heights | 5/6 | 10/11 |

| Warren | 5/6 | 10/11 |

On average, Michigan has about 140 days between the first and last frost. So, when planting peppers, tomatoes, and other vegetables, you can follow the planting schedules below.

FAQs

Answer: Ann Arbor, Michigan, is on the USDA Hardiness Zone 6.

Answer: You will find Grand Rapids, Michigan is USDA Hardiness Zone 5 and 6.

Answer: Midwest Planting in Michigan’s Hardy Flowers and reliable plants determined by the USDA is in Zone 5 with some parts in 6.